May 28, 2015 9:37 am What I Learned From Reggio Emilia

Reggio Emilia burst upon the early childhood scene in 1991 when Newsweek described their schools in Northern Italy as “the best early childhood experience in the world.” Suddenly educators everywhere were studying their philosophies and practices.

There was a lot to study: books, videos, tours to the schools, conferences led by Reggio educators in the U.S. Throughout, the Italians told us, “Don’t try to copy us. You have to find your own projects based in your own culture.” And they were right. We can’t bring the children to fields of poppies so they can study and paint them. We don’t live surrounded by Renaissance buildings, nor do we have magnificent sculptures and fountains in every piazza. Our culture is not steeped in antiquity. It is less than 400 years old, more scientific and technological than aesthetic in orientation.

But the two basic tenets of the Reggio philosophy apply worldwide. First, the child is seen as powerful, competent and worthy of respect, a marked difference from thinking of children in terms of what they don’t know and can’t do yet. Second, the adult is a co-learner with the child. These two beliefs totally change the child/adult relationship.

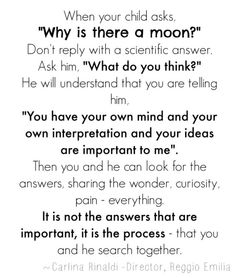

To respect a child, we have to listen to him more than we talk at him. We have to take his ideas, his theories about why things happen, his many questions seriously. When we notice that he wants to understand something, we help him to figure it out by posing open-ended questions, and setting up situations for trial and error learning. We support his research process. This is the meaning of the adult as co-learner: we don’t tell him the answers, but act as if we are exploring and discovering together. We have two-way conversations. We encourage, and when he figures it out, we are as excited as he is.

To respect a child means we don’t shout at him or shame him when he falls short of our expectations. We don’t embarrass him by saying his ideas are silly or wrong. We don’t force a pre-set curriculum on him. We don’t try to get everyone “on the same page.” We don’t tell him he’s fine when he’s scared or upset or hurt. We don’t interrupt him when he is engaged, just to stick to our own timetable. We don’t tell him we finished studying transportation last month when he is still fascinated by trains and trucks.

We enable exploration, even when it is messy. We follow his interests. We write down his ideas and read them back later to see if he has changed his mind or had further insights. We provide him with pictures and tools. We encourage him to try things out, and then revise his thinking.

Respect… careful listening… quiet voices… conversations, rather than lectures… thoughtful provocations rather than answers. Encouragement, exploration, investigation, discovery. The philosophy works in schools, and it works at home. It works in life. For all our cultural differences, what I learned from Reggio Emilia changed the way I think and act with children profoundly.

Marianne Riess is the former head of the Putnam Indian Field School in Greenwich, CT. She has 40 years of experience in working with young children.